(Italian pronunciation: moo-zay-oh del oh-pear-ah del dwoh-moh)

Enter under a bust of Cosimo de' Medici

9:00 to 19:30, Monday-Saturday;

Sunday, 09:00-13:40; closed September 8

6,00 euro

Enter under a bust of Cosimo de' Medici

9:00 to 19:30, Monday-Saturday;

Sunday, 09:00-13:40; closed September 8

6,00 euro

The Museum of the Opera del Duomo originates in the quarters which originally formed the headquarters of the Magistrature of the same name, founded at the end of the thirteenth century to supervise the undertaking of the new church of Santa Maria del Fiore. There, in a palace to the rear of the present site of the Museum, were created the sculptures designed to be placed on the exteriors of the Duomo and in particular the facade. These works show the effect of the many conflicting projects for the appearance of the Duomo, resulting in removals and changes of plan and concluding in the completion of the facade in the last century. The present museum was founded in 1891, and since then has continued to receive the works of art removed for conservation reasons from the exterior of the Duomo and the Baptistery. The collection is thus the best guide to the various changes in Florentine official sculpture over the centuries. An outline emerges as follows, from the need felt at the end of the thirteenth century to replace the old Santa Reparata with a large new cathedral. This new Duomo was to demonstrate the moral and civic strength of the city, and so the most prominent architect of the period Arnolfo di Cambio was selected. Significantly, he also worked as a sculptor, and many of the pieces in the Museum were made by him for the facade which was unfinished at his death in 1302. The Duomo facade remained only partially complete until 1587, when the Grand Duke had it dismantled on the advice of the architect Bernardo Buontalenti as part of an urban plan to refurbish Florence, with the idea of substituting a modern one. As it turned out, it was only completed in 1871 by de Fabris despite many plans and competitions among famous architects in diverse periods. Its appearance is far from Arnolfo's original design, and as it was impossible to gather all the original sculptures on the facade, these are preserved in the Museum.

Apart from this basic group of Arnolfo works, the Museum also houses fourteenth century sculptures from the Campanile by Andrea Pisano (c. 1290-c. 1349) and pupils, together with those from the Porta della Mandorla on the right side of the Duomo. Like the sculptures of Nanni di Banco (1380,'90-1421) and Donatello (1386-1466) made for the Campanile and the Duomo, the two large "cantorie" or singing galleries by Luca della Robbia (c. 1400-1482) and Donatello represent a particularly important moment in Florentine Renaissance sculpture designed for an architectural setting; they come from inside the cathedral. Also here are found other sculptures of the sixteenth century showing the continued interest in completing the cathedral through the centuries. A recent addition is a room containing tools and working materials recovered during restoration of the cathedral and the cupola which evoke the work of the masters of Brunelleschi's period.

Entrance

· Michelangelo carved his David here in 1501-4 – courtyard

has been remodeled to create an elegant entrance

· On right – Etruscan cippus, 1st half of the 5th century

B.C.- musicians and dancers

· Left side – fragments of Imperial Roman funerary art –

from campanile and cathedral

· Fragments of sarcophagi with cupids – 3rd century A.D.

· Sarcophagi showing myth of Orestes – Clytaemestra pursued

by the Erinyes

Room of Tino di Camaino

· Busts of three virtues: Hope (ivy crown), Faith (crown),

and Charity or a Sybyl (cornucopia)

· Fragments from south door of baptistery – bust of Jesus

in Benediction – head of John the Baptist

The Passage

Luca Di Giovanni da Siena, Angel with Rebeck (ca. 1388)

Andrea Pisaon, Angel with Bagpipes (ca. 1388)

Jacopo di Piero Guidi, Angel with Viella (ca. 1385)

Jacopo di Pieo Guidi., Angel with Cymbals (ca. 1383)

Room of the Old Façade of the Duomo

Arnolfo di Cambio, Madonna with the glass eyes

· Saints Reparta (oil lamp symbol of virginity) and Zenobius

(in Episcopal vestments) flank her

· hieratic pose reflects Byzantine tradition

· Solid, realistic physicality relates it to Giotto paintings

· eyes made of vitreous paste,

· “above the main doorway of the Cathedral “there stood a

fair and beautiful aedicule, in which was a marble image of Our Lady seated

with the Child, who with most beautiful grace was sitting on her knee,

and she had shining eyes which seemed real as they were made of glass”

– Anonymous writer

· The Operai took a different view: they judged the statute

“monstrous and ridiculous, as it has eyes of glass, and hideous proportions.”

Arnolfo di Cambio, Boniface VIII

· protected and defended Guelf communes against the empires

· sits stiffly on his throne like an Egyptian God

· Dante places him in Purgatory among the simoniacs – “Servant

of the servants,.” - “the great priest – may ill befall him” –-“the

prince of the new Pharisees.”

· Bull Unam Sanctam (1302) affims supremacy of spiritual

over temporal power

· four evangelists including a Donatello St. John

· Roman sarcophagi and Etruscan cippus carved with dancers

Piero di Giovanni Tedesco, Angel with a lute

Piero di Giovanni Tedesco, Angel with an oganetto

Roman sarcophagus, 2nd century A.D.

· 3 scenes from the myth of Phaeton

· Guelf eagle, cross of People, lily of Florence

· Upside-down fox – symbol of defeated Pisans and a small

Farnese lily

Room of the Paintings

Master of Bigallo, Scenes from St. Zenobius

· panel made from miraculous elm tree

Reliquary

· contain tools used by 15th century masons; also models for

the Duomo

· Brunelleschi's death mask

· several hack Mannerist models proposed for the façade

in the 1580s

· San Girolamo's jaw bone

· part of Saint Agathe’s veil

· John the Baptist's index finger

· St. Philip's arm

· a few links from St. Peter’s chain

· 16th century Libretto, a fold out display case of saintly

odds and ends, all labeled

Stair Landing

Michelangelo, Pietà

· theme: perfection of Christ's Passion and symbol of human

suffering in the face of death

· intended for his own tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome

· four figures in pyramid arrangement

· supposedly Michelangelo took a hammer to Christ's arm -

assistant (Tiberio Calcagni) repaired and finished part of Mary Magdalene

and Christ - left leg is missing - right hand and left elbow spoiled

· Nicodemus supposedly Michelangelo's self portrait - emaciated,

shows the pained face of an old man

Upper floor, Room 1

contains the two choir lofts (cantorie) of Donatello and Lucia della Robbia

Luca della Robbia, cantoria E-67

· carved in crisp white marble; decorated with colored glass

and mosaic

· placed above the door of the North Sacristy of the Duomo

- removed in 1688 for the marriage of Ferdinand de' Medici to Violante

of Bavaria - present ones are of stone

· the 10 panels depict Psalm 150

Alleluia. Praise ye the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary, praise Him in the firmament of his power. Praise Him for His mighty acts, praise Him according to His excellent greatness. (singers with book and scrolls)

Praise Him with the sound of the trumpet; praise Him with the psaltery and the harp. Praise Him with stringed instruments and organs. Praise Him upon the loud cymbals; praise Him upon the high sounding cymbals. Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord. Alleluia.

(players of trumpet, psaltery, cithern and timbrel; dancing putti, players of organ, harp and lute, players of tambourine and players of cymbals)

· laughing children dancing, singing and playing instruments

· Apollonian in calm and beauty - absence of the dramatic

Donatello (1433-38), Cantoria BBC-100

· Placed over door of Old Sacristy

· look like frenzied participants in some primitive ritual

- Dionysian frenzy

· light and color form columns covered in mosaics

· dynamic movement by explosion of joy and vitality of putti

Donatello, Mary Magdalene (c. 1453-55) T-145; BBC-98

· originally for Baptistery

· lifesize polychrome wood depiction

· ascetic penitent, body racked and emaciated yet full of

human dignity

[The following two excerpts were based on the idea that Mary Magdelena was a reformed prostitute.]

This wooden sculpture of the reformed prostitute who washed the feet of Jesus in the house of a Pharisee, dried them with her hair and rubbed them with oil, was created between 1453 and 1455 in Donatello's late period after his stay in Padua. The medieval Legenda aurea, by Jacobus da Voragine, had a considerable influence on art; in it Mary Magdalene, the chief witness of Christ's resurrection (John 20, 1-18), sought her salvation in the loneliness of a wilderness which some sources considered to be southern France.

The penitent is clad in a shaggy fur robe and is leaning on her left leg, with the right leg slightly to the back. She is holding her hands in prayer in front of her chest. Her sunken eyes, broken teeth and bony hands all emphasise the exhausted ascetic appearance that Donatello wanted to produce. Her skin, which has been tanned and dried by the elements, together with her high cheekbones and long hair, suggest her once legendary beauty and sensuousness. Her hair is also a symbol of her reverence for Christ and her penitence, and its loose, unbrushed appearance shows that she has renounced all worldly vanity. Many pictures on this theme in Quattrocento Florentine art were influenced by Donatello's sculpture.

The figure used to be in the Baptistery in Florence, although it is not certain if that was also its original position. After the Arno flooded in 1966, it was necessary to do some restoration work, and this exposed the original colour; it also gave her back the former aesthetic appearance of her body. Toman, ed., The Art of the Italian Renaissance (195-6) c

Between two rose-colored marble columns stood Donatello’s wooden Magdalen in old age. In one shocking moment I saw it all. An emaciated figure with wild, hollow eyes in deep eye sockets, and sunken cheeks, ravaged by time in the wilderness, her hands close together, praying. She was barefoot, standing with thin legs widely placed, naked, not artfully nude, clothed only in tangled hair that reached to her knees. Only two teeth stood like tiny headstones in her gaping mouth. Her shriveled legs so far apart and her clenching toes rooted her to earth while she longed for Heaven. I shuddered. The Passion of Artemisia

· a confluence of feminism, biblical research and pop culture

has placed Mary Magdalene in the front rank of Jesus’ first followers

· one of the first disciples – maybe the most beloved

· witnessed Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, rallying

the depressed and disbelieving male disciples

· portrayed in art as a prostitute transformed by Christ’s

forgiveness

· received her reputation as a result of erroneous sermon

preached in 591 by Pope Gregory the Great

· finding reversed by Vatican in 1969

· Gospel of Mary (2nd century) offers a view of Christianity

that describes an interior spirituality

· salvation is not something that comes from an external

saviour, one has to seek salvation within (King)

· Jesus as a teacher, not a saviour

· alternate voice to I Corinthians and I Timothy which urge

silence and submissiveness of women

· may have been a rival to Peter

· Mary Magdalene was a normally flawed human who came from

an ancient goddess-worshipping tradition, probably Egyptian. In certain

rituals, such as the anointing of Jesus, she [Pickett] believed Mary became

the goddess, while Jesus became the chosen god.

Bibliography

Brown, Dan, The Da Vinci Code

George, Margaret, Mary, Called Magdalene

Meyer, Marvin, The Gospels of Mary: The Secret Tradition of Mary

Magdalene, the Companion of Jesus

King, Karen L., The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First

Woman Apostle

Picknett, Lynn, Mary Magdalene: Christianity’s Hidden Goddess

STATUES FROM THE CAMPANILE – THIRD ROW

NORTH SIDE

Andrea Pisano, Tiburtine Sibyl

Andrea Pisano, David

Andrea Pisano, Solomon

Andrea Pisano, Erythraen Sibyl

These sculptures, by Andrea Pisano, remained in place on the west side until 1464, when they were moved to the north side to make room for the ones by Donatello. Rather than statues in the round, these are very high reliefs, left unfinished at the back where they were concealed by the niches. . . These subjects allude to prophecies of the Redemption taken from the Old Testament and from pagan antiquity; the two sibyls were in addition believed by medieval Florentines to have uttered obscure prophecies about the birth of Florence. With the fluid rhythm of the drapery and the careful treatment of the surfaces, the four statues are still gothic in feeling.

SOUTH SIDE

Maso di Banco, Moses

Andrea and Nino Pisano, Prophet

Master of the Scaffolding, Prophet

Maso di Banco, Prophet

A greater sense of volume and a more classical style characterise the four PROPHETS . . . which at one time stood in the niches on the south side. They are thought to date from between 1334 and 1341.

EAST SIDE

Donatello, Beardless Prophet

· a portrait of Brunelleschi [?]

Nanni di Bartolo, Bearded Prophet

Donatello and Nanni di Bartolo, Abraham and Isaac

Donatello, Il Penserioso

Sculpted between 1408 and 1421, these statues represent PROPHETS and PATRIARCHS with profound realism and massive intensity. The only images whose subject is certain is the group showing Abraham about to sacrifice his son Isaac.

WEST SIDE

Between 1420 and 1435 the last four statues were made for the Campanile. The final side to be decorated should have been the north side, but it was decided to move Andrea Pisano’s statues there and to replace them on the west side with the new ones.

Nanni di Bartolo, Prophet (ca. 1425)

· holds scroll with “ECCE AGNUS DEI (John the Baptist?)

· “Donatello” signature is of later date

Donatello, Jeremiah (1427-1435)

· model for Michelangelo’s David

JEREMIAS is another of Donatello’s works characterized by profound psychological penetration. The head of the prophet, turned to the left, is expressive of intense bitterness, with its down-turned mouth and tension in the muscles of the neck. Unlike the Habacuc, the drapery shows considerable movement: there are two great folds, an upper one which leaves the breast partially uncovered, and a lower one which accentuates the movement of the left leg. The statue, too, was popularly believed to portray an enemy of the Medici, Francesco Soderini, whose descendant Piero became Gonfalonier of the Florentine Republic, and was a friend of Niccolò Machiavelli. The Opera del Duomo Museum in Florence

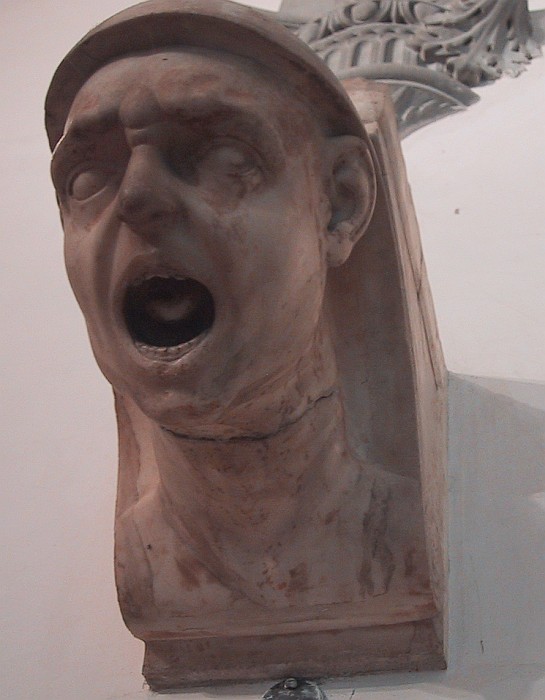

Donatello, Habbakuk T-64, T-66; BBC-98

· zucca = squash; zuccone = a big squash, a pumpkin head,

a fat head

· these realistic heads are seen today in the working quarters;

people with gnarled leathery neck

· in face – weariness, resignation grim resolve

· should be seen up from below – lie on your back on the

floor and look up to see in proper perspective

The emaciated, ascetic form of the prophet is wrapped in a long tunic, falling from the left shoulder, the deep folds of which are expressive of inner torment. The half-open mouth seems about to utter terrible prophecies. According to popular tradition Donatello used as his model for the statue of Habacuc an enemy of the Medici family, Giovanni Chiericini. The Opera del Duomo Museum in Florence

. . . The payment records of the cathedral workshop mention two statues produced by Donatello for the location during these years and one of them – the latter of the two – is specifically called Habakkuk. The name of Jeremiah has been applied to one of the statues on the basis of a later and spurious inscription on its scroll. The statue, affectionately dubbed Zuccone by the Florentines because its bald head resembles a gourd (zucca in Italian), has consequently been identified with the Habakkuk of the documents. Though we cannot be absolutely sure which statue belongs to which set of payments, the distinction is academic and the Zuccone will doubtless be known by its nickname for all time.

What is essential is the psychological intensity that Donatello has invested in these figures. The physical presence and inner animation of the Saint Mark and the Saint George have been so amplified in the Zuccone and the Jeremiah that they represent a sculptural milestone. It is not surprising to learn from later sources that Donatello is supposed to have sworn “by the Zuccone” and, while he was working on it, to have angrily commanded the figure to speak. Such anecdotes, however unreliable, are based on the psychological realism of these figures, a realism so great that they seem to be living presences with human souls.

Zuccone looks down at the pavement with his lips parted, as if prophesying to a crowd far beneath him. He is divinely inspired, but inspiration fills this face with a frightening, almost manic intensity. This is the first of several works by Donatello that are marked by a psychologically complex, profoundly troubled realism. Not even the enormous drapery folds, falling with such energy and grandness of scale, distract attention from the head of this prophetic orator, who appears to serve as a conduit between the unfathomable and the human. Andres, The Art of Florence (400-1) c

Donatello, Beardless Prophet

CAMPANILE PANELS

Andrea Pisano - hexagonal panels from Campanile (Spiritual Progress

of Man)

· campanile Plan: redemption of man after original sin

· history of mankind seen as history of salvation

Man, driven out of the Garden of Eden, in the midst of a nature now hostile, has to reconquer his dignity through toil. The panels, "true encyclopaedia of human toil and knowledge", lead us through the activities of man, represented either by their mystical inventor or more directly by straightforward depiction:

First Row - human labor

West Side: early history of man according to Genesis and the discovery of the mechanical arts as related in the Bible and classical mythology

· Creation of Man: Adam (Genesis 1:26)

· Creation of Woman: Eve (Genesis 2:27)

· Work of the Forefathers: Adam breaks the earth with a mattock;

Eve wields a distaff (Genesis 3:23)

· Animal Husbandry: Jabal, the “father of such as dwell in

tents” (Genesis 4:20)

· Music: Jubal, the “father of them that play upon the harp

and organs” (Genesis 4:21)

· Art of the smith: Tubalcain, “a hammerer and artificer

of every work of brass and iron” (Genesis 4:22)

· Farming: Noah, who “began to till the ground and planted

a vineyard” (Genesis 9:20)

South Side

· Astronomy: Gionitus

· Art of building or Scaffolding

· Medicine: a physician seated on a cathedra inspecting a

sample of urine

· Hunting or Horse Riding: a horseman throwing a stone

· Wool Working or Weaving

· Legislation: Phroneus, mythical King of Argos

· Mechanics: Daedalus, the personification of techné,

which for the Greeks was a combination of art and technology

East Side

· Navigation

· Social Justice: Hercules has just slain the cattle thief

Cacus (liberation of the earth from monsters)

· Agriculture: Homogirus

· Drama or the Art of Festivals and Spectacles: chariot symbolic

of circus

· Architecture: Euclid shown drawing

North Side

· Sculpture: Phidias carving a nude

· Painting: Apelles

· Harmony: Tubalcain striking notes on the anvil (perhaps

Ptolemy)

The transition from the mechanical to the liberal arts brings man one step further on the road to redemption, which can be achieved through the saving grace of the Sacraments. The panels showing the five liberal arts, designed at a later date by Luca della Robbia, are:

Liberal Arts

· Grammar: Priscian or Donatus and pupils

· Logic and Dialectics (Philosophy): Plato and Aristotle

in discussion

· Rhetoric or Poetry (Music): Orpheus taming animals by improvising

verses set to music

· Geometry and Arithmetic: Euclid and Pythagoras

· Harmony with Tubalcain hitting the anvil to produce the

first sounds

Upper Level - Superhuman powers (planets, Virtue and Liberal Arts - natural, moral and spiritual forces)

· Rhomboid bas-relief tiles with a blue majolica background - Andrea Pisano and workshop

West Side (Planets symbolic of cosmic virtues)

· Saturn: holds the the wheel of time

· Jupiter: holds symbols of the Christian faith: crucifix

and chalice

· Mars: an armed cavalier

· Sun or Apollo: holding a sceptre and solar disk

· Venus: supporting a pair of lovers in her right hand

· Mercury: zodiacal sign of Gemini

· Moon: seated on the waters with a fountain in her right

hand (tide influence)

South Side – Virtues as moral forces

· Faith: chalice and crucifix

· Charity: a heart in her right hand; a cornucopia in her

left

· Hope: wings spread; hands folded in prayer

· Prudence: two heads; one old, one young; a serpent and

looking glass

· Justice: sword and scales

· Temperance: diluting wine with water

· Fortitude: wrapped in a lion’s skin with a club and shield

East Side – Intellectual Forces – Liberal Arts

· Astronomy: holds an astrolabe

· Music: holds a psaltery

· Geometry: holds a book and compasses

· Grammar: holds a scourge; teaches three boys

· Rhetoric: holds a sword and shield

· Logic: holds a pair of shears

· Arithmetic: shown counting

North Side - seven sacraments – Means of Salvation

· Baptism: grandmother holds baby at fount; a priest

baptizes; putto with cornucopia = grace and abundance

· Confession: kneeling penitent; priest absolves –

base: head of a Fury, symbolic of the soul’s disorder

· Marriage: groom places ring on finger; priest in

center; 4 witnesses – trilobal ogival arch refers to solidity of marriage

· Priesthood: special shape to fit door; priest reads formula

of consecration over ordinand

· Confirmation: mitred bishop anoints forehead of child;

godmother holds – base: head of Hercules is symbol of investiture as a

“soldier of Christ” conferred by the sacrament

· Eucharist: elevation of Host; acolyte assists: base – lion’s

head = Christ’s supernatural strength

· Extreme Unction: a skeletal invalid lies on deathbed, priest

anoints breast; acolyte reads prayers for dying; another holds a candle

– base; eagle, symbolic of soul’s flight towards heavenly bliss

Baptistery Removals

Silver altar (1366-1480)

· 12 panels in silver and translucent enamel enclosed in

late Gothic frame

· above altar frontal is silver-leaf and enamel cross - holds

relic of the True Cross

· Made by Florentine goldsmiths - scenes from life of John

the Baptist

· Artists include Andrea del Verrocchio, Antonio del Pollaiolo,

Bernardo Cennini

· Michelozzo - contributes central statue of St. John

Antonio Pollaiuolo

· 27 needlework panels once part of priest's vestments

Byzantine mosaic miniatures (12th century)

Giovanni del Biondo, St. Sebastian triptych

· May be record for arrows - saint looks like a hedgehog

Ghiberti, Baptistery Panels E-66

· 8 original panels from Gates of Paradise

· 10 panels in original, cast in bronze and fired with gold

· Helpers - Michelozzo, Gozzoli and Cennini

· Doors commissioned 1425 by Arti di Calimala, patrons of

Baptistery

· 27 years work

· replaced doors of Andrea Pisano which had faced the Duomo

· By its side is a small bust of Brunelleschi

· Illustrate new idea of representation in perspective coupled

with a study of anatomy

· Ghiberti adopted Donatello's stiacciato technique - using

a painter's art to depict real volume of the figures in perspective, a

different technique altogether from the traditional bas-relief method

Exit area

· contains a drawing of his ornate, sculpture-filled façade: removed by Medici in 1587

April 26, 2002

Whoever She Was, Her Sins Were Forgiven

By GRACE GLUECK

One of the most beloved but baffling characters in Christian theology is Mary Magdalene, who in the New Testament is described as an early and devout follower of Jesus. He is supposed to have cast out seven demons from her, and she is said to have mourned at the foot of his cross and to have been the first witness to his resurrection. What other role she had in relation to him has never really been clarified.

But over the centuries, in the minds of theologians, artists, churchgoers and the secular public, this wildly popular saint has been tagged with many other personas and stereotypes: as a prostitute, a courtesan and femme fatale, a penitent, a muse, a teacher and preacher, a well-groomed fashion plate and a wasted hag in rags. She has been dealt with in countless works of art, in books, plays, music (including opera) and movies. A scantily clad Jacqueline Logan played her in Cecil B. DeMille's "King of Kings" (1927), and the Greek actress Melina Mercouri took the role in "He Who Must Die" (1957).

In our day she has been most widely perceived as a reformed prostitute who cast herself in penitence at the feet of Jesus. Yet in 1969 the Roman Catholic Church formally revised the canonical identity of Mary Magdalene to fit with the early Christian description of her as a faithful follower and first witness, and not, as tradition long held, the unnamed woman cited in John 8.1:11 as the adulteress saved by Jesus from public stoning.

But who was she, really? There are no fewer than seven Marys in the narrative of Jesus, and she has been confused and conflated with more than one of them. Now a small but intriguing show at the American Bible Society, "In Search of Mary Magdalene: Images and Traditions," sets out not only to untangle her from what has been called the "muddle of Marys," but also to explore, through art from the 14th century to the present, the many identities thrust upon her.

In her catalog essay, the show's guest curator, Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, adjunct professor of liberal studies at Georgetown University, writes that the Magdalene's religious importance has been to serve as "a classic image of the redemptive and transformative nature of Christian faith," turning the abstract concepts of sin and forgiveness into realistic human experience. As a transgressor saved by the healing love and forgiveness of Jesus, she was a source of spiritual encouragement for other sinners.

Whatever their truth, the dramatic stories woven about her have made her artworthy even to this day. The exhibition, which includes devotional images in manuscript illuminations, paintings, sculptures and prints, also displays examples of Magdalene imagery from secular sources, including film stills, book jackets, posters and CD covers.

The devotional images are arranged thematically according to the guises in which the Magdalene is most often presented: sinner, penitent, witness, contemplative and muse.

Over the centuries a set of signature attributes by which she can be identified has developed: an unguent jar (sometimes a perfume bottle, a glass carafe or a liturgical vessel) containing the oils she used to anoint Jesus; long, flowing red hair (red signifying venality) either smartly coiffed or hanging raggedly in tresses; elaborate gowns or rags; pearl-like teardrops flowing from an eye; and a crucifix, a skull and a book.

In her "penitent" guise, she appears at her most melodramatic here in Carlo Dolci's painting "The Penitent Magdalen" (circa 1670). With teary eyes and mouth agape she looks to the heavens, hands clasped in prayer. A skull and a jar sit by one elbow, and a flow of red hair falls in ripples from her head. As seen by Dolci and other Italian Baroque painters, Ms. Apostolos-Cappadona points out, the Magdalene at penance "upheld the Roman Catholic teaching on and practice of the sacraments."

On the other hand, a century earlier, the Magdalene is a model of the cool and collected high-born worshiper in "Portrait of a Noble Lady Reading Her Prayer Book" (circa 1520) by the Flemish artist known only as Master of the Parrot.

She is dressed in black velvet, accented by a red velvet shawl. Her red hair is bound close to her fair, round face and partially concealed by a cap trimmed with jewels. An elaborate gold cross on a gold chain rests on her bosom. Her Magdalene identity is established not only by her hair color and the luxurious gold unguent container that sits on the table before her, but also by the Book of Hours she is reading, evidence of the dutiful attention to daily spiritual devotions that marked those in search of salvation.

In this painting the Magdalene is seen in her "contemplative" mode, a concept developed long after the New Testament period by conflating her with Mary, the sister of Lazarus, who took instruction at Jesus' feet. Lazarus' sister thus became an emblem of spirituality, serenity and otherworldliness. With the melding of the two Marys, depictions of the Magdalene as a contemplative became part of her iconography.

Other striking images in the show include the 16th-century Flemish painter Adriaen Isenbrant's "Penitent Magdalen." In it, atypically, she reclines, poring over a book in a wilderness setting. She is dressed like a classical goddess in a draped garment that slips away to reveal her breasts, only partially covered by a tumble of red-gold hair. In the sky hangs a golden miracle, her ascension to Heaven.

Her ascension was also depicted by Albrecht Dürer in "Mary Magdalene

Carried to Heaven" (1504-05), a magnificent woodcut depicting the saint

clasping her hands in prayer as her hefty nude body is hoisted over her

rocky cave retreat by a swarm of tiny angels. In dynamic contrast, a Magdalene

much attuned to earthly pleasures is depicted in an exquisite engraving

by the Dutch painter Lucas van Leyden, "Dance of St. Mary Magdalene" (1519).

It shows a mature Magdalene in stylish dress and a halo escorted by an

equally stylish gentleman to the center of a kind of love fest, in which

music is played, couples embrace and other

allusions to sexuality are rife.

There are some very recent works in this show, among them "I've Seen Love Conquer the Great Divide" (1989), a large but stiffly painted oil by an American, Wendy Brusick Steiner. It portrays the Entombment, with Mary Magdalene, supported by Mary, wife of Cleophas, embracing Jesus' feet as he is prepared for burial by Mary, his mother. There are several stencil prints by a Japanese artist, Watanabe Sadao, whose heavily stylized imagery takes cues from Byzantine and medieval art. And there are, of course, those film stills and book jackets.

This show can only suggest the complexities of Mary Magdalene's many identities, but it and its catalog do very well on a rather lean diet of images. Most of its viewers will know a lot more about this appealing figure on leaving than when going in.

``In Search of Mary Magdalene: Images and Traditions'' is at the American Bible Society, 1865 Broadway, at 61st Street, Manhattan, (212)408-1500, through June 22.