(Floor Plan, B-200) E 90-91

Piazza San Lorenzo - 055-216 634

10:00-17:00 (closed Sundays except for Mass: 08:00, 09:30, 18:00)

Admission: 2.50 euro

· parish church of Medici family

· 1419: Brunelleschi rebuilt church in Renaissance Classical

style

· façade was never completed

· huge dome by Buontalenti echoes that of Brunelleschi's

Duomo

· 1740: bell tower built

Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bronzino, Donatello, Filippo Lippi – some of the greatest names of the Renaissance have had a hand in this magnificent Florentine church. San Lorenzo was the parish church of the Medici, so naturally it attracted the best and brightest of the period. Look particularly for Il Martirio di San Lorenzo, which seems to revel in the torments of the flesh, and for the exquisite pulpits designed by Donatello, where the fiery ascetic Savonarola once preached. Florence in Your Pocket

INTERIOR T-44

· circular marker of Cosimo il Vecchio's burial site is in

front of the chancel E-90

· Cosimo is buried below within a pier supporting the floor

· Donatello is buried close to Cosimo

· burial slab formed in polychrome marble

· design, based on a combination of geometrical shapes (circle

and square) favored by the humanists, is attributed to Verrocchio

Francesco Landino’s Tomb

second chapel on the right as you enter from the rear

Deprived of the light, Francesco, whom alone music extols above all others for his great intellect and his organ music, rests his ashes here, his soul above the stars.

The musician's figure with an organetto is a notable example of the sculpture of the period. In the border we see two angels, one playing a viol, the other a lute. Above the head is the Landini coat of arms, a pyramid with six golden mounds on a field of azure, with three branches of laurel protruding from the mounds.

Giovanni da Prato, Il Paradiso degli Alberti (1389)

· clearer than the Decameron in clarity of description of

the Florentine circle in which music was performed

· describes daily activities in the Alberti villa

· interspersed among philosophic discussion are stories,

novelle, told by various characters, among whom is Francesco

· each tells a story typical of his own occupation

· Francesco’s story is about a musician serenading a fair

lady in the evening; he is overheard by a local despot, who is so entranced

by the music that he takes the musician into his service. Complications

arise when this service is neglected for the charms of the fair lady

Book III - Interlude

Francesco played his love verses so sweetly that no one had ever heard such beautiful harmonies, and their hearts almost burst from their bosoms.

. . . when all were gathered in the garden, much to the pleasure of all, and especially of Francesco, two young maidens appeared who danced and sang his Orsu, gentili spiriti so sweetly that not only the people standing by were affected, but even the birds in the cypress trees began to sing more sweetly.

. . . another time the organ was made ready and brought to Francesco . . . everyone marveled at his playing.

Book IV

. . . after one of the stories when the sun was coming up and beginning to become warm while a thousand birds were singing, Francesco was ordered to play a bit on his organetto to see if the singing of the birds would lessen or increase with his playing. As soon as he began to play many birds at first became silent; then they redoubled their singing, and, strange to say, one nightingale came and perched on a branch over his head. When he had finished playing, the question was raised whether one creature had the power of listening more than another in view of the fact that the one nightingale appeared to hear the sweetness and harmony of Francesco's music more than another bird which happened to be there.

Donatello, Pulpits (1460) BBC-106-7; E-91; T-145

· Donatello began work on the bronze pulpits in the nave when

he was 74 years old

· They depict Christ's Passion and Resurrection

· the pulpits are used only during Holy Week. On the southern

pulpit the events proceed from the Agony in the Garden to the Entombment

- from the Sacrifice to the promise of Salvation. The symbolic sacrifice

of the Eucharist performed at the high alter is the culmination of the

program. The reliefs on the northern pulpit show the fulfillment of Salvation

in Christ's actions after the Crucifixion.

Pietra Annigoni (1910-88), St. Joseph and Christ in the Workshop E-91

· one of the few modern artists to exhibit in Florence

Bronzino – Il Martirio di San Lorenzo (1569) E-90

· huge mannerist fresco

· study of the human form in various contorted poses

Old Sacristy T-43; E-90

· sculptural decoration by Donatello in the form of stucco

reliefs and bronze doors are later additions

· these additions mitigate some of linear and planar purity

of Brunelleschi's architecture

Cappella dei Principi/New Sacristy

Piazza Madonna degli Aldobranci – 055 238 8602

08:15-17:00

closed Monday, except every second Monday

and Sunday, except every second Sunday

Entrance fee: 6 euro includes admittance

to New Sacristy of Michelangelo

The pavement in front of the sarcophagi contains arms of subject cities of the Grand Duchy inlaid in polychromed marbles, mother-of-pearl, coral, and lapis-lazuli. Great pieces of porphyry and fragments of fine antique marbles were dragged to Florence, where captured Turkish slaves were put to work sawing up the stone into manageable pieces. All this great richness was not only because the chapel was intended as a dynastic mausoleum for the Medici, but also it was hoped to include the very tomb of the Saviour Himself from Jerusalem – a plan that failed in the end only because the savvy Pasha refused to sell such a valuable tourist attraction. Borsook, The Companion Guide to Florence (205) c

· Duke Cosimo I conceives as a mausoleum for self and descendants

· ground plan based on Baptistery and Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem

– a domed octagon

· designed by Don Giovanni de’ Medici (Cosimo I’s illegitimate

son), Buontalenti and Giorgio Vasari

· built by Nigetti and others (1605-1737)

· cupola décor by Benvenuti (1828-36)

· Francesco wants to make mausoleum a showplace of rare Tuscan

minerals

· encourages development of the art of inlay work in pietre

dure

· Francesco used this style for the geometrically patterned

floor of his Tribuna in the Uffizi

· He had collected chalcedony, green quartz, sardonyx, agate,

and jasper for eventual construction of tombs

· this medium is associated with Romans, early Christians,

Byzantium, Romanesque Italy and now modern Tuscany

· Lorenzo had also been fascinated with precious gems and

minerals

· Ferdinand, 3rd Grand Duke - sets up a workshop, the Opficio

delle Pietre Dure

· famous in Rome for his hedonistic life of gambling and

entertainment

· sober and conservative as Grand Duke

· undertakes a vast building program characterized by quantity,

not brilliance

· sponsors lavish court fetes and theatrical productions

· art evolved from geometric inlays to pictorial representation,

using a widening range of precious materials to duplicate natural coloring

Even without its intended introduction, the chapel is a breathtaking experience. Great pilasters with gilded Corinthian capitals carry a frieze binding together walls and apses and bearing in handsome Roman letters the names of the grand dukes. Beneath each name is a tomb, one per wall and one in each of the apses (the actual burials are in the crypt below). Each has an immense porphyry sarcophagus, on a scale that competes with those of Constantine's mother and daughter in Rome, covered in Michelangesque fashion with a broken pediment. A cushion in the center of the lid supports a huge replica of the grand duke's crown, a pedimented niche above holds his monumental effigy, and over his name, a cartouche between flaming urns bears the Medici arms. The ducal arms are inlaid in the floor, and those of the cities of Tuscany adorn the socle of the walls. The rest is a riot of geometric inlay work in antique and modern marble, porphyry, lapis lazuli, gemstones, mother-of-pearl, coral, and more - a veritable encyclopedia of rare and beautiful stones. The architecture that it covers is planar and faceted in order to accommodate the relatively small plaques of precious materials. Octagonal piers at the openings to the apses are reminiscent of those on the corners of the Campanile, both in their form and in their small-scale decoration. But the revetment of the Campanile is more restricted in vocabulary, more festive in color, and more subservient to the architecture it adorns. The darker polychromy of the chapel has more of the Roman richness and sobriety of the Pantheon and the Baptistery. The geometric patterns in the chapel, however, do not serve the architectural order as they do in those famous models. The elaborate inlaid decoration seems, in fact, to exist for itself, competing in an odd way with the colossal architectural scale and order and tearing apart the rationalism and clarity of the design.

The result is a building famous and infamous as one of the most remarkable and costly funerary monuments ever erected. It was described by an early critic as one of the wonders of the world, and by another as a residence for Harlequin. Particularly since the advent of neoclassicism in the second half of the eighteenth century, its critics have tended to be less than charitable. Today, closed off from the church of which it was to have been a part, it has been reduced to an amazing vestibule that must be crossed by the thousands of daily visitors to the Medici Chapel next door. Seen in immediate juxtaposition to the pure colors, distinct forms, power, and integrity of Michelangelo's incomplete masterpiece, the Cappella dei Principi appears oversized and gaudy, an eternal witness to the fact that impressive scale, craftsmanship, and materials do not guaranteed beauty. . .

In their self-conscious efforts to create splendid form, grand associations, and accessible and polyvalent meaning, the artistic experts who created Ferdinando's Cappella dei Principi quoted from Florence's entire architectural heritage. Perhaps they loaded the chapel with more associations and meanings than one building could comfortably bear. The Holy Sepulchre, the Pantheon, the Baptistery, Brunelleschi's dome, Santissima Annunziata, the sacristy of Santo Spirito, the Medici Chapel, Florence as the New Jerusalem, Florence and the Medici as the revivers of the eternal glory of Rome - all come flooding in on the student of Florence who stands in the amazing memorial. Indeed it is a building far more interesting and significant as the summation of a glorious past that was drawing to a close than as a prophecy of creative things to come. The awesome tradition that it closes makes all the more poignant and appropriate the words uttered by Grand Duke Ferdinando as he lifted the shovel to break ground for this great agglomeration: "Here will be our end." G. M. A., The Art of Florence

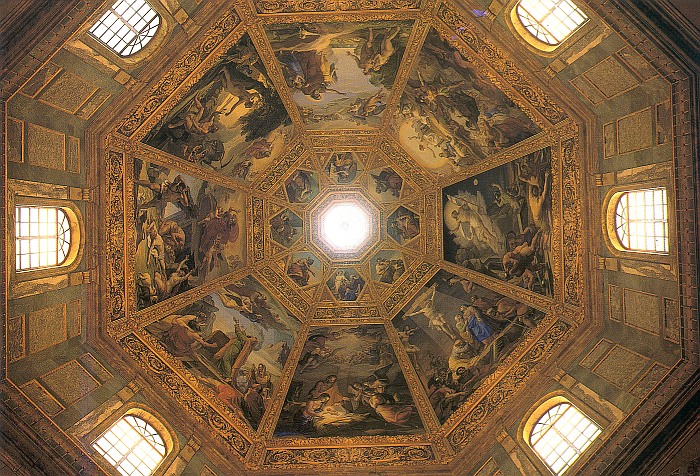

Cupola of the Chapel of the Princes

The Chapel of the Princes was built by the architect Matteo Nigetti (1560-1649) in 1604-1640 to the designs of Don Giovanni de' Medici, a member of this family who practiced architecture in a semi-professional way. The mausoleum is a rare example in Florence of the Baroque style, and its huge cupola and lavish interior were conceived as monuments to the greatness of the Medici. Its sumptuous octagonal interior was conceived to hold the grand ducal tombs and is completely covered with hard stones or marble, mainly of foreign origin; the princely sarcophagi are completed with bronze statues of the Grand Dukes set into niches. The execution of the inlay in hard stones lasted for three centuries; the process of covering the walls, mainly carried out in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was fraught with problems on account of the difficulties of working the materials and their very high cost. The cupola should originally have had an internal covering of lapis lazuli, but was left incomplete at the end of the Medici period and was frescoed in 1828 by Pietro Benvenuti with scenes from the Old and New Testaments at the command of the reigning house of Lorraine.

The Medici Chapel

(The New Sacristy) E-91

Madonna - Even though it is not finished in all its parts, one can distinguish in the act that it has remained unfinished . . in the imperfection of the unfinished stone the perfection of the work." Vasari

The Medici Chapels form part of the monumental complex of San Lorenzo, whose building history lasts from the first years of the fifteenth century until the early seventeenth. The church of San Lorenzo was the official church of the Medici from their period as private residents in their palace in Via Larga (now via Cavour), becoming their mausoleum up to the time of the extinction of the line. Giovanni de' Bicci de' Medici (died 1429) was the first who wished to be buried there with his wife Piccarda in the small Sacristy of. Later, his son Cosimo the Elder was buried in the crossing of the church. The project for a family tomb was conceived in 1520 when Michelangelo began work on the New Sacristy, corresponding to the Old Sacristy by Brunelleschi on the other side of the church. It was all Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, future Pope Clement VII who wished to erect a mausoleum for certain members of his family, Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano, and Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino and Giuliano, Duke of Nemours. The architecture was complete by 1524, its white walls and pietra serena interior based on Brunelleschi. Michelangelo continued to work on the sculptures of the sarcophagi until 1533, but the only ones actually completed were the statues of the Dukes Lorenzo and Giuliano, the allegories of Dawn and Dusk, Night and Day and the group of Madonna and Child placed above the sarcophagus of the two "magnifici" and flanked by Saints Cosmas and Damian. The latter were executed by Montorsoli and Baccio di Montelupo, pupils of Michelangelo. As a result of the complex history of the chapel and its elaborate symbolism, many interpretations have been made of its sculptures. The poses of the two principal figures represent the Active and Contemplative lives while the famous statues on the sarcophagi probably refer to the conditions and phases of human life. The tombs also refer to the liberation of the soul after death, a philosophical concept closely linked with Michelangelo's own spirituality. In 1976, numerous drawings and sketches by Michelangelo executed, as was often the case on walls, were discovered in a small space beneath the apse and sacristies of the church. These drawings, fifty-six in all, show legs, feet, heads and masks, and may be related to the statues and architecture of the Sacristy.

x x x

. . . the chapel has an aura of restraint and sobriety that is at variance with Michelangelo's original intentions. The central bay of the south wall should have contained a double wall tomb and more statuary. Today we see only a statue of the Madonna and Child, resting on an unadorned platform and flanked by the Medici patron saints Cosmas and Damian. The tombs on the east and west walls were also meant to have additional sculpture. Crouching nude youths and trophies would have adorned the lintels where we now find garlands carved in relief. River gods were planned for the spaces beneath the sarcophagi, and other figures were intended for the blank niches that flank the seated effigies. In the upper reaches above the wall tombs and in the cupola, frescoes would have greatly enriched the imagery and decorative splendor of the chapel.

. . . The labyrinth that today's visitor must negotiate from the street and the later grand-ducal mausoleum to the Medici Chapel is so tortuous that the latter now appears to be a hermetically sealed sanctum in a way that Michelangelo never intended.

. . . the chapel was constructed to house the tombs of Cosimo Pater Patriae's two grandsons, Lorenzo il Magnifico and Giuliano, together referred to as the magnifici, and the tombs of Cosimo's last legitimate male descendents who were not churchmen, Giuliano, duke of Nemours and Lorenzo, duke of Urbino. . . A fifth member of the family, the bastard Alessandro who ruled Florence as duke from 1530 to 1537, is also buried there. He shares the sarcophagus of the younger Lorenzo, who may have been his father , though Clement is also a candidate for that role..

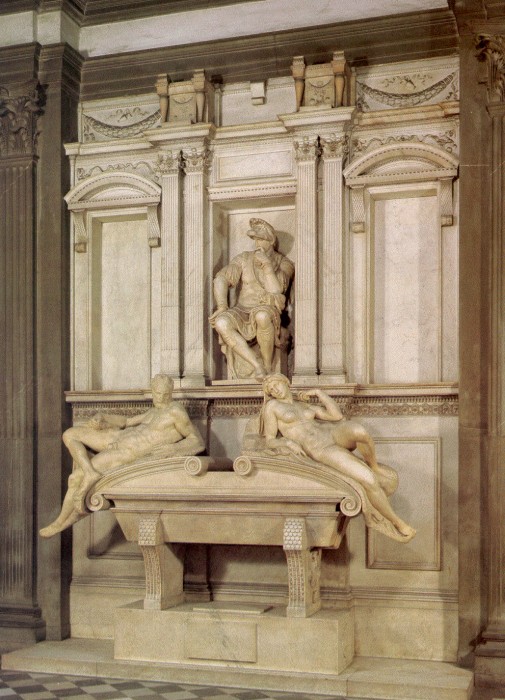

. . . The tombs of the younger Giuliano and Lorenzo, though unfinished, are appropriately grand and dignified. The effigies of both of the departed dukes are clothed in classical armor, worn more for its allusive qualities than as an indication of the activities that had characterized their lives. Lorenzo had once served as commander of the papal army, however, and Giuliano, after his death, had lain in state dressed in armor. The figure of Giuliano holds a baton and Lorenzo wears a classical helmet - details that further emphasize their ceremonial roles as captains of the church and Roman patricians.

While both figures are seated facing frontally with their heads turned to one side, they are nevertheless a study in contrasts. Everything about Giuliano's effigy suggests enormous potential energy, as though it were a seated counterpart to the giant David. The powerful body is arranged in a spiraling contrapposto pose, and the disposition of the legs, with the knees at different heights and the left foot drawn in under the body, suggests that the figure is about to stand. Lorenzo, on the other hand, seems lost so deeply in thought that his body has been drained of any possibility of action. With one hand raised to his chin in a pensive gesture and the other turned outward, resting against his thigh, he appears to have directed all of his energies inward. His ankles are crossed so that he could not stand without first changing the position of his feet. While Giuliano's thrust-back shoulders and thrust-forward chest create an undeniable sense of extroversion, Lorenzo's rounded shoulders and sunken chest reflect the profound introversion with which Michelangelo imbued this effigy.

Although certain features of the statues coincide with historical facts, these are by no means accurate portraits of the two dukes, either physically or psychologically. Giuliano's alert and aggressive pose is as alien to his personality as is Lorenzo's pensive and contemplative demeanor. Giuliano was, actually, a typical victim of the younger-brother syndrome. His eldest sibling, Piero, was destined to govern, and it was always assumed that the second brother, Giovanni, would have a career in the Church. There was in fact, very little for Giuliano to do. He became a gracious and likable princeling, but never a decisive enough personality to be of much use in promoting his family's ambitions. After the expulsion of 1494, he enjoyed considerable personal popularity while residing at the courts of Mantua and Urbino, and Castiglione even made him a protagonist in The Courtier. Lorenzo, on the other hand, was a much livelier man than his uncle. He commanded the papal army for a time, and Machiavelli dedicated The Prince to him. Michelangelo's characterizations of the two dukes are so different from their historical personalities that it has even been suggested that the statues are misidentified. In one of his notes concerning the chapel, however Michelangelo associates Giuliano with the personifications of Night and Day that rest on his sarcophagus, which confirms the traditional identification of the figures.

Because of the undeniable differences between the two statues, it has often been claimed that they represent "the active life" and "the contemplative life," a long-standing theoretical polarity in humanist circles. Although it is possible that this contrast entered into Michelangelo's conception, there is no proof that it did. A recorded statement by him sheds some light on the issue. According to a contemporary, he claimed that he did not make realistic portraits of Giuliano and Lorenzo, "but gave them a greatness, a proportion, a dignity . . . which seemed to him would have brought them more praise, saying that a thousand years hence no one would be able to know that they were otherwise." These words suggest that Michelangelo intended to create august, highly idealized portraits, which would flatter the dukes, raise them to a quasi-mythical realm of princely apotheosis, and in the process grant them immortality based on earthly fame. This is wholly in keeping with the imagery of the time and with the desires of the Medici family at this stage of their history.

Beneath the effigy of each duke is a sarcophagus on which recline the personifications of two phases of the daily temporal cycle. Here Michelangelo paired opposites - Day and Night beneath Giuliano, Dusk and Dawn beneath Lorenzo - and gave each pair contrasting male and female personalities. Of these figures, only Night has identifying attributes. She wears a tiara with a moon and a star, while beneath her left thigh is an owl, and her left foot rests on a bundle of poppies. All of these symbols are quite obviously and traditionally associated with night. Only the mysteriously sinister and beautifully carved mask beneath her left shoulder defies a straightforward explanation.

Although each of the personifications has its own individuality, they also share certain traits. None of them is conventionally finished; indeed, in the whole chapel only the effigy of Giuliano has had all of its chisel marks polished away. The personifications have powerful nude bodies composed spirally about a horizontal axis. And yet, like the Saint Matthew and the four unfinished Captives, they seem overcome by oppressive but undefined external forces that confine them within narrow boundaries and contort the postures of their limbs. An all-consuming weariness has invaded their intrinsically muscular and healthy bodies, and reduced them to states of incapacity and helplessness.

Night alone of the four is represented sleeping, appropriately enough, but her slumber seems disturbed by some vague torment. Despite her decidedly masculine musculature, hers is the body of a mature woman, identified as a mother by the stretch marks of childbirth across her abdomen.

The massiveness of Day's body and its internal torsions are derived from the antique fragment known as the Belvedere Torso, which Michelangelo had studied in Rome. Although marks of the claw-tooth chisel and occasional polished surfaces both appear on his body, Day's head remains a roughly hewn mass of stone. His body is that of a mature man, and his pose complements Night's without echoing it.

Just as Lorenzo's effigy is characterized by inaction, so too are Dusk and Dawn, his accompanying personifications, less decisive than those that represent Night and Day. Dusk is a mature male figure whose body is less massive and whose unfinished head is more fully realized than that of Day, his masculine counterpart. Dawn, across the tomb from Dusk, is the most intriguing of the four reclining personifications. Her body, though robust in proportions, is more conventionally feminine than that of Night, and characterized by a soft, youthful, perhaps virginal perfection. But more than the other personifications, she seems beset by an overwhelming sadness. The huge diadem that holds her veil in place seems to weigh down her head, and a band beneath her breasts fetters her body.

If Michelangelo had completed the ducal tombs according to his original intentions, reclining river gods would have rested on plinths beneath the sarcophagi, facing in the opposite direction from the Times of Day. Although these figures were never begun in stone, full-scale models were made in clay. Two of the models were installed along with the marble sculptures in about 1550, and a fragment of one has survived to this day in the Casa Buonarrotti. Like the Times of Day, this god is heroic in proportion, and his body twists around a horizontal axis.

Whether the river gods were meant to symbolize particular rivers is by no means certain. If so, were they the four rivers of Paradise, or earthly rivers? We know that in 1513, when Giuliano and Lorenzo were inducted into the Roman patriciate, reclining river gods were placed on the platform erected on the Capitoline for the ceremony. On that occasion they were identified as the Tiber and Arno, the rivers that flow through Rome and Florence, and which were symbolically united by the Medici papacy. Michelangelo's decision to include river gods on the tombs must surely relate to that event, but the exact meaning of the figures in the context of the Medici Chapel has never been discovered.

The discussion so far has focused on aspects of the Medici Tombs that are understandable in secular terms. Religious considerations are also crucially important, as becomes apparent when the tombs are considered in the context of the chapel. Although the south wall never received its intended double tomb, a Madonna and Child by Michelangelo would have dominated that ensemble. This is one of his most inspired and exalted compositions and "grandeur" is the only word that seems sufficient to describe the effect it produces. The Virgin is one of Michelangelo's profoundly sad Madonnas, well aware of her Son's tragic fate, while the Christ Child is an infant of Herculean physique who turns to his mother for protection and nourishment. The torsions noted in the other statues also characterize these figures and determine the interaction between them.

The figures of the dukes turn their heads in the same direction, giving the chapel an unmistakable sense of direction and focus. The traditional assumption has been that Giuliano and Lorenzo are gazing at the Madonna. It has been pointed out that they actually look toward the original entrance door to the left of the Madonna (Gilbert 1971), but this observation does not alter the directional impetus that causes the spectator to concentrate on the south wall. The Madonna and Child would have been the focus of the double tomb ensemble, even if the gazes of the dukes were not meant to rest on them. And there is no question but that the statues of the Medici patron saints, Cosmas and Damian, (carved by two of Michelangelo's followers, Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli and Raffaello da Montelupo, after designs by the master), reinforce this sense of focus by their interaction with the Madonna and Child. Furthermore, the only point from which the whole chapel can be comprehended at once is the altar - more specifically the space behind the altar, where the priest would stand while saying Mass for the souls of the deceased. From there, more than from any other point, the Madonna and Child are emphatically the focus of attention.

The frescoes planned by Michelangelo would have additionally emphasized the importance of the south wall. A fresco of the Resurrection, the central miracle of Christ's life, was to appear above the double tomb. Catholic churches and chapels are traditionally dedicated to a particular saint or a mystery of the faith. This chapel is dedicated to the Resurrection, a doubly appropriate choice. Giovanni de' Medici, the original patron of the chapel, had been crowned as Pope Leo X on Easter Sunday; the feast of Christ's Resurrection, and the dedication therefore recalls this special event in his life and in the history of his family. Furthermore, references to the Resurrection are traditional in funerary imagery and in tomb chapels, because of the promise of eternal life that it established for all believers. Despite the numerous secular motifs, then, the central theme of this chapel is resurrection - both Christ's as a historical event and that of the dukes and the magnifici in the future.

The chapel was more than a repository for the bodies of the deceased Medici and the site of their apotheosis through Michelangelo's sculpture. Services were also performed here for the salvation of their souls. In a papal bull from November 17, 1532, Clement VII provided for those services in perpetuity, with three masses a day, interspersed with continuous readings of psalms and prayers on behalf of the dead. (This routine was observed until 1629, when Urban VIII partially released the monks of San Lorenzo from the burden.) Such a provision, unique during the Renaissance, was probably planned from the beginning of the project for the chapel. Both the appearance of the chapel and its liturgical function, then were conceived with lavishness and an extravagance appropriate for a papal family whose members had achieved the status of royalty.

From what we know about Michelangelo's creative process we would expect that some relatively simply unifying concept, or concetto, underlies the symbolism of the chapel. The apotheosis of individuals and a mighty family is surely crucial, as is the hope of resurrection. But if a single idea can be distilled from the images in this chapel, it is the concept of time inexorably sweeping away all earthly things. The marble figures on the sarcophagi symbolize the endless recurrence of the times of day. Endless too was to be the vigil of prayer and masses performed by living men carrying out the terms of Pope Clement's bull. Whoever entered the chapel would have been greeted by the silent stares of the dukes, directed toward images of the Madonna and the Resurrection, and confronted by the four personifications of the time cycle. This mental and aesthetic experience would have been accompanied by the sound of priests' voices reading prayers and psalms or reciting the words of the Mass in an eternal plea for the salvation of the deceased Medici.

On more than one occasion Michelangelo himself suggested that this sort of concetto, relating time, death, and immortality, informed the program of the Medici Chapel. Condivi reports that the master had intended to carve a mouse to accompany one of the personifications, for the mouse, like time, "ceaselessly gnaws and consumes." Michelangelo also composed a somewhat oblique text concerning the imagery of the chapel:

Heaven and Earth, Night and Day speak and say: "With our swift course we have led Duke Giuliano to his death. It is just that he has taken his revenge as he has done, and this is his revenge: after we had killed him, thus dead, deprived us of the light, and with his closed eyes he sealed ours so that they no longer shine upon the earth; what, then, would he have made of us had he lived?"

The cycle of Night and Day and the passage of time bring death even to the greatest. But the expression of this idea is followed by a passage of rhetorical flattery of the highest order. Duke Giuliano's passing is such a loss, Michelangelo suggests, that it has diffused the force of the very temporal cycle that destroyed him. The reference to "unseeing eyes" is fascinating because it calls to mind the fact that none of the figures carved by Michelangelo for this chapel have incised irises or pupils; all are reduced to the state of blindness suggested by his text. The cycle of time may destroy all things, but Michelangelo's words suggest, in keeping with the apotheosis theme of the chapel, that certain great individuals are able to overcome it. Though they pass on to eternal life in the heavenly realm, through fame and glory - and, in the case of the Medici, through Michelangelo's brilliant concetto for this funeral chapel - they attain a state of earthly immortality as well. J.M.H, The Art of Florence (1015-1020) c

Tombs of Giuliano, Duke of Nemours and Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino

summary

Theme: The overcoming of the earthly prison of life, either through the contemplative life (Lorenzo) or the active life (Giuliano)

Giuliano, Duke of Nemours

Ei Dì e la Notte parlano, e dicono:

Noi abbiàno col nostro veloce corso

condotto alla morte el Duca Giuliano:

é ben giusto ch’è ne faccia

vendetta come fa. E la vendetta ´questa:

che avendo noi morto lui, lui così morto

ha tolto luce a noi e con gli occhi chiusi

ha serrato é nostri, che non replsndono

più sopra la terra. Che avrebbe dunche

fatto di noi, mentre vivea? Michelangelo

[Day and Night speak and say: With our swift passage we have led Duke Giuliano to his death. It is right that he takes his revenge as he does. His vengeance is this: We have slain him, and now that he is dead he has taken the light from us. His eyes are closed and he has fastened ours so they can no longer shine upon the earth. What then would he have done with us while he lived?]

· Giuliano recognized for liberality (coin in left hand)

· He sits on a stool covered with drapery in manner of a

victorious Roman general sitting in his triumphal chariot

· His head is turned sharply to our right

· features resemble those of Michelangelo’s subjects (curly

hair, oval face, strong cleft chin)

· cuirass decorated with monstrous mask (bat with a human

face)

· hands rest lightly on a staff of office

· left leg flexed; about to rise – a man of action

· universal theme of the relationship between Man and Time

· sarcophagus abstract and unadorned in form

· Night and Day are Michelangelo’s most famous statues

Night and Day BBC-280

· Day turned sharply to wall - we see heavy back and side

· Night: displayed to onlooker

· legs modelled in opposite positions

· poses echo chiasmus (inverted relationship) of classical

sculpture - forms animated by counterbalanced limbs

· unbroken flowing line between two statues = uninterrupted

and inexorable passage of Time

Night

The following poem was addressed to Michelangelo on the subject of the symbolic figures around the monument of Giuliano of Nemours: (Giovanni Battista Strozzi)

La Notte, che tu vedi in sì dolci atti

dormir, fu da un Angelo scolpita

in questo sasso, e perché dorme, ha vita,

destala se non ‘l credi, e parleratti.

[The night, which thou seest sleeping in such graceful pose, was by an angel wrought in this stone; though asleep she lives; rouse her if thou doubtest it, and she will speak to thee.]

Michelangelo replied:

Caro mi è il sonno, e più l’esser di sasso

mentre che il danno, e la vergogna dura;

non veder, non sentir, m’è gran ventura;

però non mi destar; deh, parla basso.

Non ha l’ottimo artista alcun concetto

che la materia in sé non circonscriva

col suo superchio, e solo a quello arriva

la man che ubbidisce all’intelletto.

[Sweet is sleep to me and even more to be of stone, while the wrong and shame endure. To be without sight or sense is a most happy change for me, therefore do not rouse me. Hush! Speak low.

The greatest artist has no concept which is not already contained within the marble, and it can be reached only by the hand which obeys the intellect.

· body rests on drapery, in a deep and troubled sleep - left

arm twisted behind back

· leans against hideous mask which represents an evil nocturnal

spirit

· a barn owl under her bent leg - more sinister night creature

than the screech owl; its claws scratch a bunch of poppy heads (allusion

to darkness and sleep)

· curiously arranged hair falls in long plait onto her breast;

it is held back from her face by a diadem in the shape of a crescent moon

with an 8 pointed star at its center

· suggests transience of night and makes allusion to haunting

obsessions and creatures that are associated with darkness

· an oncologist believes that Night’s left breast shows signs

of breast cancer; therefore, the symbols associated with night are symbols

of death as well as of night

Day:

· muscular, mature man at height of powers

· pose reminiscent of images of the rivers in classical sculpture

· exaggerated contrapposto of contorted body, especially

in twisted arms

· bearded face left unfinished

· did Michelangelo intend to express the non-finito - does

a concept need to be finished in every detail?

Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino

· Machiavelli’s Prince was dedicated to him

· Lorenzo was a politically mediocre figure who little resembles

the noble figure described by Machiavelli

· his helmet looks like a wolf or bear; this zoomorphic head-dress

might be a symbol of his insanity

· it casts a shadow over his face

· he wears the armor of a victorious Roman general – seated

on a ceremonial chair

· his left hand hides his chin

· his left elbow rests on a closed box perhaps symbolizing

Parsimony – this is considered a characteristic of a thoughtful person

(an extrovert is considered generous)

· or does it rest on the armrest of the chair?

· his legs are relaxed and crossed – the stillness of the

pose indicates that he is lost in thought

Dusk (on the left)

· a mature man, more naturally posed than the other figures

· his right leg is crossed over the left; his limbs look

heavy with fatigue

· his head nods as he falls asleep

· his face is indistinct in the gathering darkness

· a painterly effect is achieve by leaving the stature non-finito

· the surface of marble has been roughened (as in Day) to

give a duller, shadowy appearance

Dawn (on the right)

· successful and sensitive

· a young woman waking from a deep sleep, rising from a couch;

covered in a cloak

· a slight movement of the body accentuates her unhealthy

languor as she awakes

· movement completed by raised left arm

· the narrow band under her breasts alludes to man’s subjection

to the material – a concept expressed in the 4 prisoners or captives in

the Accademia

ArtMedicine

The Breasts of "Night": Michelangelo as Oncologist

To the Editor:

The unusual appearance of the left breast of Michelangelo's "Night," a marble statue of a female figure, has often been mentioned in the literature on Michelangelo's Medici Chapel (Church of San Lorenzo, Florence, Italy). One of us, an oncologist, found three abnormalities associated with locally advanced cancer in the left breast. There is an obvious, large bulge to the breast contour medial to the nipple; a swollen nipple-areola complex; and an area of skin retraction just lateral to the nipple. These features indicate a tumor just medial to the nipple, involving either the nipple itself or the lymphatics just deep to the nipple and causing tethering and retraction of the skin on the opposite side. These findings do not appear in the right breast of "Night" or in "Dawn," another female figure in the Medici Chapel, or in the many other depictions of women in works by Michelangelo.

Modern scholars agree that the unusual appearance of the breast of "Night" is intentional and not due to an error or its slightly unfinished state. Art historians and even plastic surgeons have argued that it reflects the artist's supposed lack of interest in or familiarity with the nude female figure. We suggest that Michelangelo carefully inspected a woman with advanced breast cancer and accurately reproduced the physical signs in stone. Even if he did not see the disease in a model, he could have studied the corpse of a woman; moreover, autopsies were legal at that time. Given that Michelangelo depicted a lump in only one breast, he presumably recognized this as an anomaly. Many doctors in his day could probably diagnose this condition in a woman. Historians of breast cancer agree that the disease and its treatment were discussed, often at length, and described as cancer by the most famous medical authorities of antiquity -- Hippocrates, Celsus, and Galen -- and by several prominent medieval authors, including Avicenna and Rolando da Parma.

For these reasons, there is a strong possibility that Michelangelo intentionally showed a woman with disease and that he may have known that the illness was cancer. If Michelangelo indeed depicted "Night" as having a consuming disease, this would complement the imagery in the Medici Chapel, help us understand his study of the female body, and add to our knowledge of the depiction and allegorical associations of illness in the Renaissance.

James J. Stark, M.D. Jonathan Katz Nelson, Ph.D.

Cancer Treatment Centers of America New York University

Portsmouth, VA 23704 50139 Florence, Italy

Biblioteca Laurenziana

Piazza San Lorenzo, 9

Tel: 055-214 443

entrance on left side of San Lorenzo

3 euro

In the Cloisters of the Church of San Lorenzo is a faire and beautifull Librarie, built and furnished with Bookes by the familie of Medici: the roofe is of Cedar very curiously wrought with knots and flowers, and right under each knot is the same wrought with no lesse Arte in the pavement. In this Library I told three thousand nine hundred bookes very fairely bound in Leather, after one sort, all bound to their seates, which were in number sixtie eight: and, which is the greatest grace and cost also, very many of the bookes were written with the Authours owne hands. There is also at the farther end of this Librarie one other of prohibited bookes, which I could not see. Sir Robert Dallington (1561-1637), Survey of the Great Dukes State of Tuscany c

The Convent adjoining [the Cappella dei Principi] and its fine old cloisters, with here and there an orange tree laden with golden produce, springing from amidst masses of ruin and rubbish, is best worth visiting for its library, the far-famed Bibliotheca Mediceo-Laurenziana. This precious collection owes its commencement to the free times of Tuscany; the first donations were from the old merchant Cosimo, his brother Lorenzo, and his son Peter. Then came the splendid contributions of the Dictators and the Popes of the House of Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent, Leo the Tenth, and Clement the Seventh. The Grand Dukes seem to have done little; and the Austrian masters of Tuscany, who succeeded to the last of the Medici, particularly Leopold, were the first, after a long lapse of years, to increase its stores: the libraries of suppressed convents enabled the latter to do so with great effect. This library was raised after the designs of Michael Angelo, and there is an air of Gothic grandeur and gloom about it that well belongs to its destination: the windows, the cornices, the architraves, the very doors, are beautiful, and an exquisite simplicity and symmetry reigns over the whole, that soon effaces the gaudy impressions of the Medician chapel, and restores the mind to those pure enjoyments, which no associations of moral degradation sully and embitter.

It is not for some time after having entered this library, and having passed and repassed along the old oaken seats carved by Battista del Cinque, and Ciapino, that one perceives, here and there, a ponderous tome, wrapped in vellum, clasped in brass, and chained in iron, on desks as curious as its own contents. Still this collection is multifarious, consisting of precious and rare MSS. in almost all known languages, illuminated with the most beautiful and curious miniatures. But most interesting than its Manuscripts of Virgil and Tacitus, its Pandects of Justinian, or its Councils of Florence, is the MS. of Boccacio’s Decamerone and of Benvenuto Cellini’s Life, to those who prize not books for the antiquity of the dust that lies on them, but for their bearings on the social history of man, and the progressive development of his nature.

On a table in the centre of this spacious hall stands a small crystal vase, covering the fore-finger of one, who had been destined to the flames of an auto da fe – of Galileo – a relic which some will kiss with as much devotion as the Majesty of Spain salutes the tooth of his patron, St Dominick. This was the finger that traced the luminous ‘Dialogues on the System of the World.’ [Galileo’s finger is now in the museum of the History of Science.] The books of this collection are all locked up in their old presses, as they were in days when books, like gems, were preserved in caskets. Among the few pictures that decorate its walls, are three original portraits of great interest and value – one of Politian, one of Petrarch, and one of Laura, by their friend Martini, whose saints were all Lauras, as Raphael’s Madonnas were all Fornarinas. Lady Morgan, Italy c